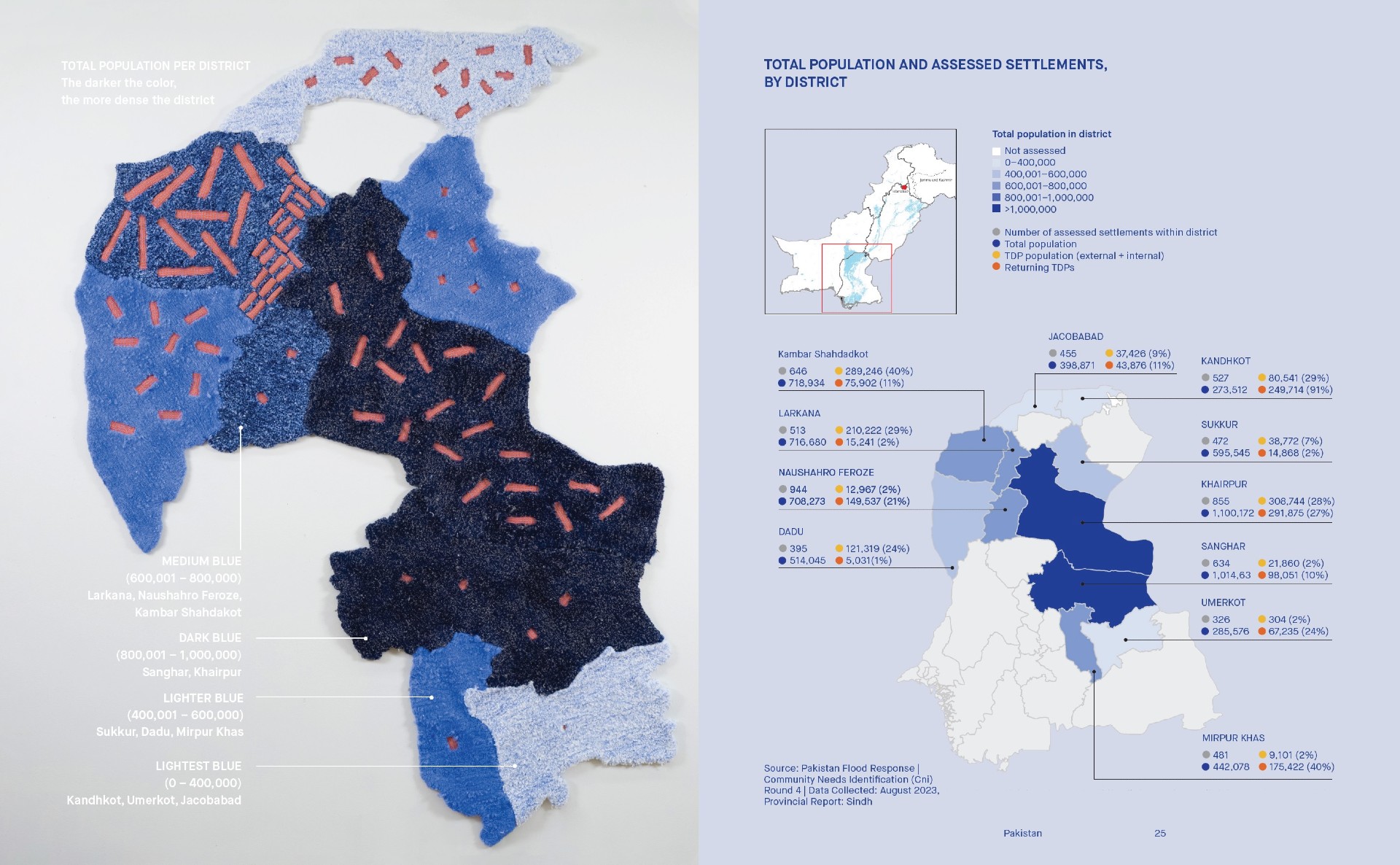

“We wanted to find a way to make the data visual and tangible, so people could connect with it more intuitively,” explain Parsons MFA graduates Jing Pei and Yichen Pan, who translated IOM’s data on the 2022 floods in Sindh, Pakistan into textiles. “Our idea grew from the intersection of climate vulnerability and environmental debt – how both people and materials can experience displacement, recovery, and transformation.”

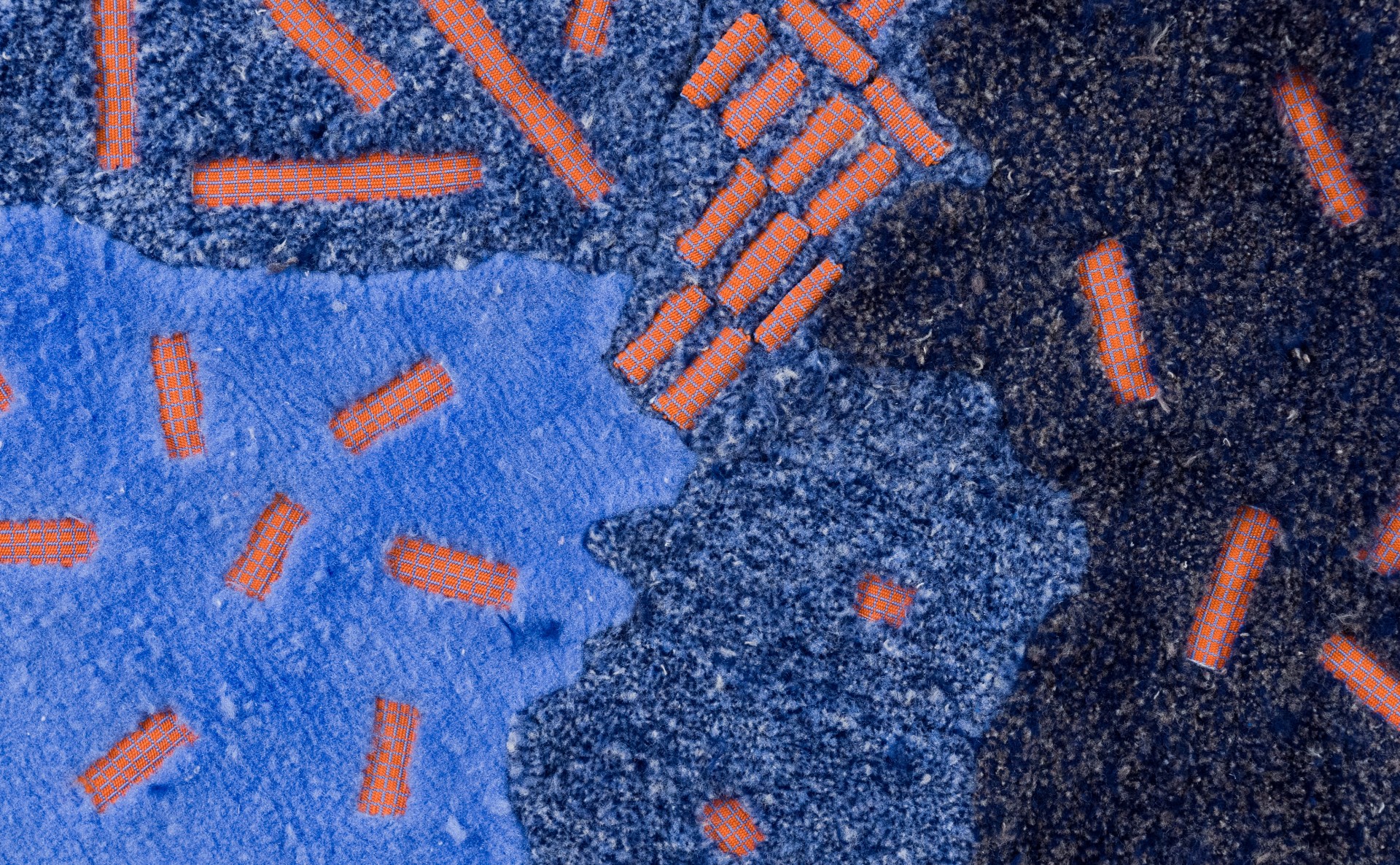

Their textile combined weaving and tufting, two techniques rarely brought together. Jing explained that she chose weaving for its inherent structure and clarity, using the krokbragd technique to create clean color blocks that could stand in for data points. Each orange woven square represented 325 displaced people.

Yichen, meanwhile, hand-tufted shades of blue yarn to build a population gradient across Sindh province. Darker blues reflected greater displacement, while lighter tones suggested areas less affected.

“We were struck by how the data reflected both the scale and the human impact,” they say. “By combining two approaches, we wanted the piece to feel layered – both technically and emotionally.”